My hidden talent is that I can see every single person as the baby that they used to be. It’s not that in mid-conversation I suddenly stop and see a tiny red wriggling baby, partly wrapped in flannel. It’s more like a sensation, like, I can feel their baby. I can feel their inside-baby. That has helped in my line of work, helped me stand still when someone is talking with me who is hard to talk with. The dad of a kid in my son’s class who complains about Mexican people crossing to take all the jobs. My former college student, J, whose face is slack on one side because of Bell’s Palsy and on the other, a round tumor the size of a golf ball along his jaw. Babies, both of them. It helps me love them more than I already would.

Crabby middle-aged women cued up for the Circle Line tour in NYC – their babies are harder to see, and real estate agents beeping the locks on their shiny cars, also difficult. But I still can, with a little effort. The work feels like a nudge. Feels like an itch I scratch. Like a skill I do mostly without thinking of, but sometimes with a tiny exertion and then it’s done.

It’s not on my resume, this skill. It doesn’t look like:

Writing teacher/workshop facilitator..Executive Director, nonprofit. Noticer of People’s Inside-Babies. But it probably should be on there. On my Linked-In Profile, maybe.

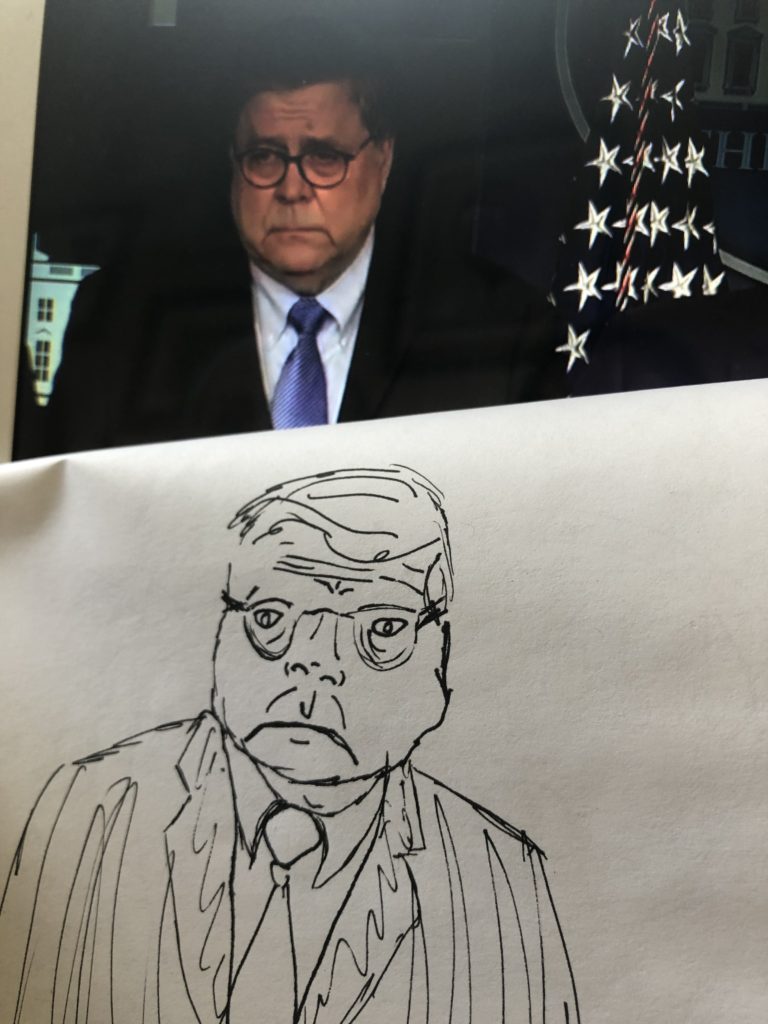

It would be harder to see Rush Limbaugh’s baby, though I think I could if I stood in the same room long enough with him. Hard to see William Barr’s little baby. The men who are soft and red and screaming already, all scarlet-faced and fists batting the air next to their heads, mouths open with a long sound coming out of them: that’s hard.

My hidden talent can’t be applied like one might a superpower. I will never use it to pull a car off of someone’s body or to douse the flames in a high rise building in the Bronx. It’s really not particularly helpful for anything besides my own work and the way it makes me feel more tender about the person, it opens up my senses a little toward them. I pay attention to the little cues they offer, like a baby who, when you tickle its cheek and it turns hungrily toward your finger, says it’s ready for a breast. Or when it begins to squirm, sometimes that means it will soon commence filling its diaper. Or when it startles because of a loud clap of something, eyes widened and mouth open, listening. Those are the sorts of cues I can read in the people whose babies I can see.

Just now, talking with you, I can see your baby. I can see the way you are hungry and the way you have held very still, listening, just now, to me.